J F Wilkinson

© Clinical Photography & Medical Illustration Services, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Manchester 2020

On 5 January 1960 John Frederick Wilkinson was worried. Approaching retirement as head of haematology at Manchester Royal Infirmary, Wilkinson (or ‘Wilkie’ as he was known) and colleagues had argued for over a decade that a specialist British society was needed for haematology but with no success.

The Americans, French, Italians, Germans and the Dutch had long since formed their own national societies and Wilkinson was clearly stung by recent conversations where the lack of a British body ‘has been a matter of comment from our European colleagues’.

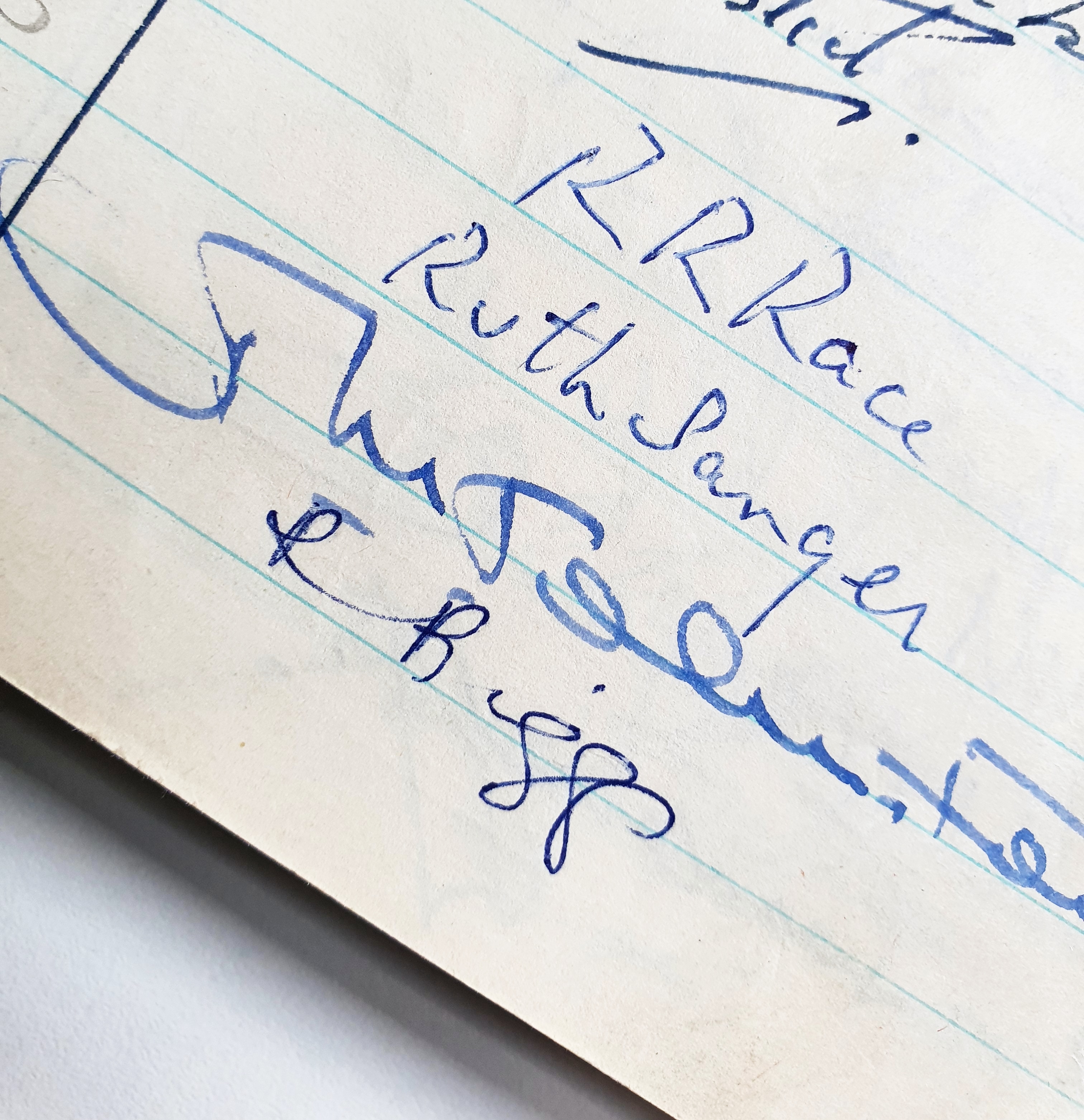

Wilkinson wrote to Leslie Witts, then Nuffield professor of clinical medicine at the University of Oxford, outlining his plan. He added: ‘Since you and I are the two most senior haematologists in the country we should initiate this undertaking’. A copy of his letter is held in the society’s archive and below Wilkinson’s typed message is a hand-written list of eight surnames, ticked and circled with the promising line ‘all agreed’.

That all-male list is a ‘Who’s Who’ of British 20th century haematology pioneers whose obituaries reveal ground-breaking research as well as a treasure trove of anecdotes. From Wilkinson himself (who trained sea-lions to defuse bombs during World War II) and Leslie Witts (writer of medical opinions in the Lancet under the pseudonym ‘Doctor Don’), the names include Royal physician Sir Ronald Bodley Scott (who loved detective novels and occasionally deployed a devasting and astringent wit); Ernst Neumark (whose skill on the accordion ‘could make a party hilarious’), New Zealander Cedric John Charles Britton (who worked his passage to England as a ship’s doctor); Robert Gwyn Macfarlane (whose snake phobia didn’t stop him discovering that viper venom causes blood clotting) and Hull-born Martin Hynes (apparently ‘noted for his very large Rolls Royce’1).

Haematologist Rosemary Biggs, later internationally renowned for her research on blood coagulation and haemostasis, also corresponded with Wilkinson. Her letter of 4 April 1960 gives strong approval for the new Society. Biggs notes the need for a body to represent British haematology internationally and for meetings to be limited to one a year. They would ‘provide the opportunity for those with laboratory and clinical interests to meet’.

Witts swiftly arranged an inaugural meeting on 19 November 1960 at the School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in London. Open to all UK haematologists, 163 attended and gave unanimous agreement to plans for the new society with a ceiling of 300 members, a ‘modest’ annual subscription of £1 and a committee with Witts presiding.

A second meeting followed in 1961 in Oxford and the archives hold a photograph of this gathering too. Seven rows of haematologists smile for the camera but of 143 photographed, only 14 are women. Bars on women studying medicine continued until 1944 when medical school funding changed to mandate a ‘reasonable’ proportion of women (‘say one fifth’), ‘progress’ that still restricted all but the strongest female candidates.

Excerpt from the signing-in book from the first meeting of BSH

© BSH

Second meeting of BSH, Oxford 1961

© Clinical Photography & Medical Illustration Services, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Manchester 2020

Pictured in the centre on the front row is Rosemary Biggs. A founding committee member, Biggs later enjoyed telling the story of Witts (perhaps humorously) complimenting her on her time as secretary and the way she did it with no paper records ever seen. Certainly none exist in the Society’s archive today and it is solely due to Howard T. Swan’s archive research in the 1980s that we can tell the Society’s foundation story.

The BSH has transformed over the decades from its foundation by a pioneering group of predominately male consultants to today’s work as the UK’s largest haematology organisation with membership across the entire multidisciplinary specialty, fulfilling Biggs’ founding aim of uniting the clinical and laboratory workforce.

Learn more about today's multidisciplinary haematology team.

1 https://history.rcplondon.ac.uk/inspiring-physicians/martin-hynes

Sources:

The founding of the British Society for Haematology, H T Swan, Archivist, British Society for Haematology (1990) British Journal of Haematology 74 (s1); 54-56.

Women in medicine: historical perspectives and recent trends, L Jefferson, K Bloor, A Maynard, British Medical Bulletin, Volume 114 (1), June 2015; 5–15.

Any other business: ‘Blood, blood, glorious blood’

One of the anecdotes collected on the BSH’s foundation is a memory that members regularly sang a tune called The Haematologist’s Song at the close of meetings.

While we have haven’t found any official recordings of this musical finale – it is clear that this is, in fact, highly probable, thanks to the musical talents of Professor Humphrey Kay (1923- 2009).

Kay joined the Royal Marsden hospital as a haematology consultant in 1956 and established ‘a collaborative approach to treatment, combining practical strategies with scientific method’. His work on the treatment of leukaemia was the start of one of medicine’s ‘great success stories of the 20th century’ and today more than 70% of children and an increasing proportion of adults can be cured.

Kay also wrote and published poetry including a parody of Flanders and Swann’s Hippopotamus Song. Switching the famous lyrics ‘Mud, Mud, Glorious Mud’ (itself borrowed from music hall favourite ‘Beer, Beer, Glorious Beer’) to ‘Blood, Blood, Glorious Blood’, Kay sang the song ‘with great aplomb’ at international haematology conferences and also, perhaps, led a rousing chorus to close Society meetings too.

Discover the full lyrics to The Haematologist's Song.

With grateful thanks to Professor Gerry Slavin who found a copy of the lyrics in his attic.

Source: Eric Watts / Humphrey Kay